Vegetable Price Dashboard

Prototype

http://vegeprice.pdis.tw

Github

https://github.com/pdis/vegeprice

Website

http://bipub.afa.gov.tw/AFABI_Open/

可交付原型、溝通協調、菜價資訊整合

可交付原型、溝通協調、菜價資訊整合

Everyday commodity prices have long been a matter of intense public concern, and because vegetable prices typically fluctuate during the typhoon and flood seasons, Premier Lin Chuan instructed the Public Digital Innovation Space (PDIS) team to help government agencies create a comprehensive vegetable price information platform before the flood season arrives in May.

This platform should allow the public to track vegetable prices and prevent the misinformation or lack of information that causes consumer panic, with information that will also help consumers choose other vegetables not affected by floods.

The PDIS team took on the challenge of integrating data across government agencies using information technology and answering consumers’ questions about why vegetable prices are so high. The information also had to be turned into structured data, on a real-time basis, without adding to the agencies’ workloads.

So we started thinking about how people understood “vegetable prices” as information—what kind of data they needed, how the government released this data, and how the media reported it. Did that process ultimately affect vegetable prices, or were psychological expectations generating undesirable outcomes?

After understanding the questions, we began collecting information and gathering feedback from field experts, the developer community and members of the media.

In the process of gathering feedback, we gradually realized the crux of the problem: the information received full disclosure, but it wasn’t structured. So although the information was available in real-time, it wasn’t integrated with other relevant data. That made it hard for experts or journalists to quickly find the information they needed. And without links to all the databases, they couldn’t analyze, report or explain the information in a comprehensive manner.

Thankfully, experts from the open-source community stepped in at that point and helped the PDIS team take stock of all the information relating to vegetable prices, and organize usable website content and open data. This included information on actual prices as well as potential factors triggering price changes such as rainfall and typhoons. We planned to release some of this information as open data, and other information in the form of webpage content.

The most direct method for promoting open data and data integration was to create a prototype application quickly, demonstrate its feasibility, and show the value of the data.

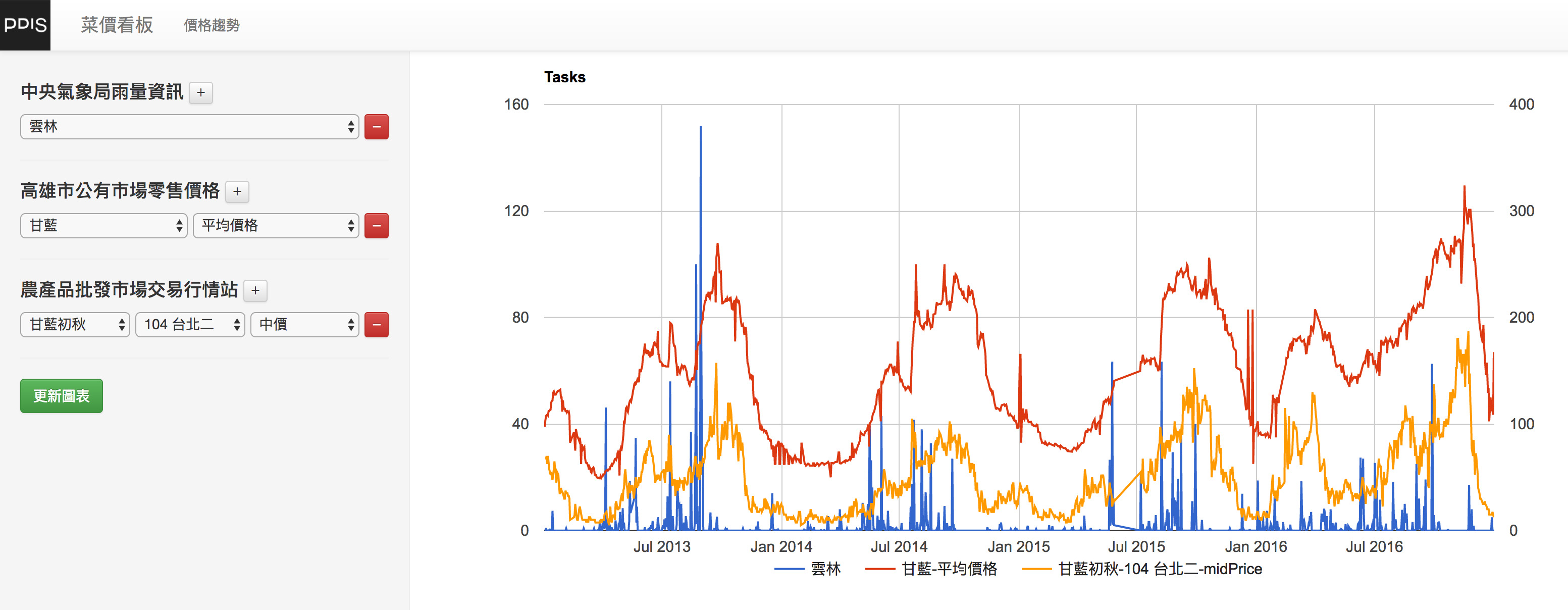

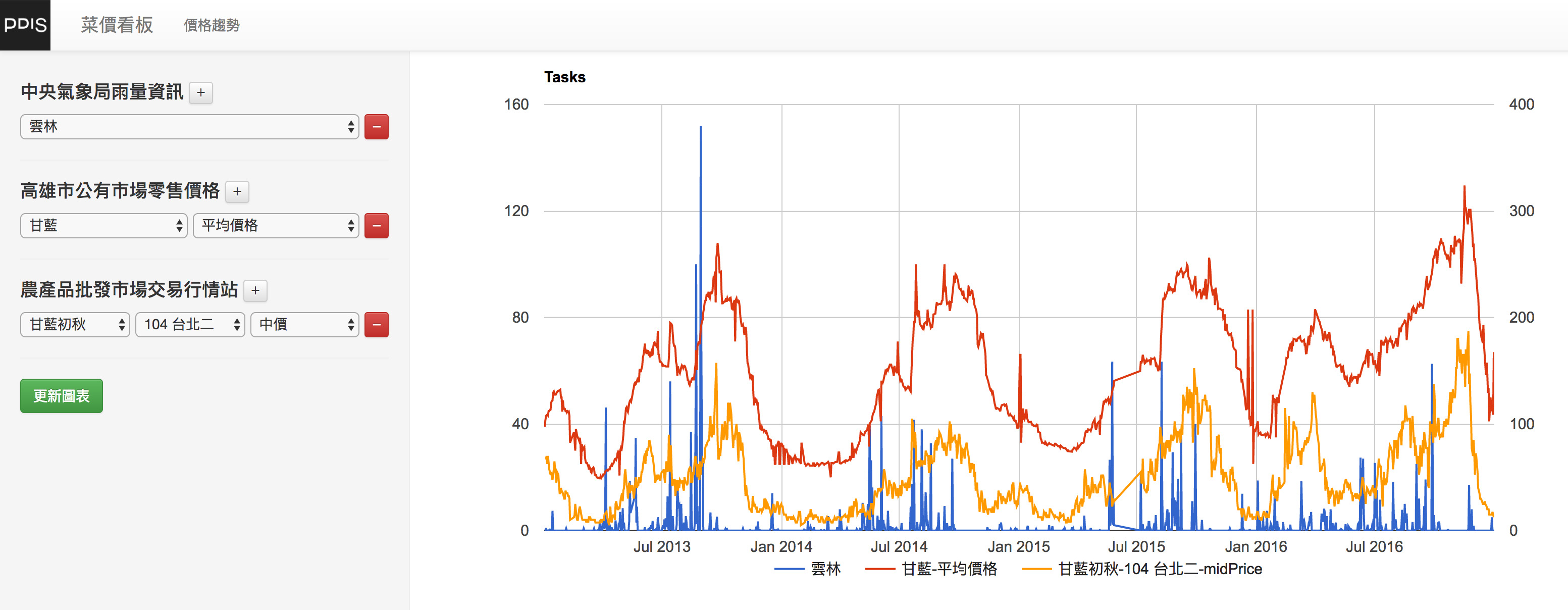

After taking stock of all the data available, we focused on precipitation forecasts and retail and wholesale market information as initial content to populate our prototype.

Interfacing with the Central Weather Bureau’s precipitation data was straightforward because the information was open, reliable and available. It was also easy to plot rainfall and vegetable prices on the same chart and see potential connections at a glance.

As we went on, however, we found some issues with data integration: each kind of vegetable was produced in a specific location, but only a real expert could name that exact location for every vegetable. Though Taiwan is not a large country, matching vegetables from one location with rainfall from another location due to poorly integrated information would be very confusing.

The PDIS team also set out to present historical wholesale and retail prices as webpage content. We quickly wrote a search program, created a three-year historical database, and put it all together with a search engine. This allowed the public to directly track prices of specific vegetables, such as cabbage, and movements in the retail and wholesale markets: prices today versus a year ago today, this month versus last month, even the last few days versus several days before that. Throughout this process, we also learned that some useful databases didn’t employ open formats, which made them inconvenient and less accessible, and a few databases couldn’t even be found on government web portals. Fortunately, the Council of Agriculture and the open source community provided the complete raw datasets so that our system could be completely integrated.

While creating the prototype, the PDIS team decided on five principles to guide contractors who will develop or operate the system in the future:

We wanted a system that’s easy to use, quick to learn, and presents information in a way that answers people’s questions. So we designed a simple user process and made sure any graphs with multiple measurements could be easily understood.

Integrating information is the platform’s biggest selling point, because it can bring data from different agencies into a single interface. And sharing the interface method also allows the public to see the processed data, which helps them understand and analyze changes in vegetable prices.

The entire source code for the prototype platform should be made public to give the community a chance to participate in the process. Doing so allows citizens to express their opinions directly in the program, and provides a reference for other developers keen to help or develop their own programs.

To make it easy for contractors to take over the platform, the system is designed to be expandable and easily integrated with other databases in the future.

The system is likely to receive heavier traffic before and after flood season. To prevent system overloads, we built the prototype with a CDN (content delivery network) framework to improve website performance, and followed the Ministry of Transportation and Communications’ PTX (Public Transport Data eXchange) platform, capable of supporting an average volume of 1 million searches a day.

At the vegetable price integration platform meeting on March 3, 2017, the COA’s Agriculture and Food Agency expertly designed 6+1 decision-making scenarios while the PDIS offered professional recommendations regarding the data framework.

After merging all recommendations, the two sides decided to create a searchable vegetable price platform before the arrival of the plum rain and typhoon seasons. The system should integrate retail and wholesale prices, temperature and rainfall forecasts, amount of vegetables stored in rotating stockpiles, and production and import volumes.

Information providers were also invited to the meeting to assess feasible data release methods. After participants exchanged views, a consensus was gradually formed to put user experience first, shifting the focus from a government decision-making system to an information sharing platform for citizens.

Meeting participants also decided not to provide real-time information on rotating stockpiles and imports, as that would involve intraday trading prices. To avoid influencing market prices, a compromise was reached to provide the previous day’s closing prices instead.

Now, a broad spectrum of information on vegetable prices can be quickly accessed through a single platform. This convenient search experience will help both citizens and professional analysts absorb information quickly.

Government agencies at all levels can also add to the data’s visual and intuitive appeal, which will make for a more persuasive tool when explaining and communicating policies to the public.

Changes in commodity prices are rarely attributable to one single factor, or even a few factors. Prices may simply change over time, or move in response to social trends, shifts in the social structure, or international developments.

Government agencies and researchers must therefore continue monitoring various trends to understand the full picture regarding price fluctuations. Constant expansion of the vegetable price system and adjustments to data presentation will be critical in the future. We therefore welcome anyone with specific ideas about data content or quality to express their opinions on the government’s open data portal.

In addition to allowing the public to check vegetable prices and the latest trends, the platform will lay a stronger foundation for open data and transparency, so that as government agencies build data-sharing platforms and coordinate data releases in the future, they can maintain an open attitude and solidify the foundations for mutual trust and cooperation with the public.

2016-11-17 Meeting for management mechanism of production and marketing of agricultural products and review of stable vegetable price (reference material)

2016-12-16 Meeting with open government deputy ministers (reference material)

2016-02-08 Meeting with Open Knowledge Foundation (reference material)

2017-03-03 Meeting for reconstruction of Vegeprice Public Information Integration Platform (transcript )

2017-04-06 Meeting for Vegeprice public information integration platform (transcript)